Some of the brightest minds at 3M, the company that invented Post-it Notes, have undertaken a tech challenge posed by Polar Bears International: They’re helping to develop a minimally invasive way of attaching a tracking device to a polar bear. The results could help polar bear scientists with critical research. BJ Kirschhoffer, our director of conservation technology, talks with us about the project and its potential.

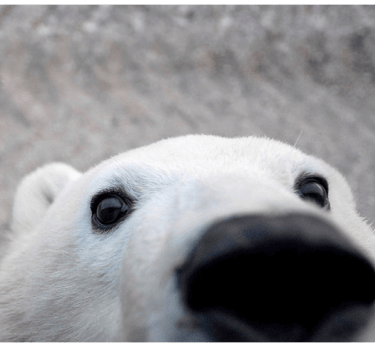

Photo: Mike Lockhart/Polar Bears International

Q & A: Burr on Fur

3M scientists are volunteering their time to help find a temporary way of attaching a small tracking device to a polar bear's fur to determine if the method is able to withstand Arctic conditions, including extreme cold, saltwater, and snow.

8 MINS

01 Aug 2022

Q: Let’s start with a little background information. Why do scientists track polar bears? How does it help polar bear conservation?

A: Tracking devices provide vital information on polar bears, allowing researchers to follow them even when they’re far out on the sea ice or wandering in 24 hours of winter darkness. Remote tracking allows us to understand the movement patterns and behavior of polar bears, along with other information such as habitat use, responses to changing sea ice conditions, and population boundaries. It’s critical data in a changing Arctic.

Q: Are there different kinds of tracking devices?

A: Traditionally, scientists used satellite collars to follow polar bears. But these can only be used on adult females. Adult males can’t be collared because their necks are as wide as their heads—the collars slip right off! Scientists also avoid collaring subadult bears because young bears grow too quickly.

To solve this problem and learn more about these important groups of polar bears, scientists have been testing GPS ear tags and implants as potential ways to track polar bears. Over time, as technology has advanced, basic GPS tags have become much smaller, opening new possibilities. As technology further improves, the tags could eventually replace the collars now used on adult females as well.

A traditional satellite collar for polar bears. These can only be used on adult female bears.

Q: Why is there a need for a new way to attach tracking devices?

A: At present, ear tags must be permanently attached, and implants require minor surgery to place the tag under the skin. Adhesive tracking devices would be temporary and non-invasive. Biologists always strive to obtain data with the least impact as possible.

Q: How did 3M get involved?

A: My father, Jon Kirschhoffer, recently retired as a scientist there—he was an advanced research specialist in the 3M Corporate Research Systems Lab. I grew up knowing all about the different kinds of tape and sticky products that 3M makes. We had drawers and drawers full of them! One of my colleagues, Geoff York, our senior director of conservation, has long been interested in the possibility of developing a tracking device that could stick to a polar bear. So I asked my dad, during his last year before retirement, if the 3M tech community could figure out how to do that and they rose to the challenge. They liked the environmental aspect and the chance to contribute to polar bear conservation.

Q: Are there any special challenges involved or hurdles to overcome?

A: There are actually quite a few special requirements that make this an interesting problem to solve. The 3M team will need to develop a way to attach a transmitter to the fur or skin of a polar bear. The method must be non-toxic and non-permanent—and it must last for seven months to a year in Arctic conditions. Further, the attachment method can’t interfere with a polar bear’s thermoregulation or damage the bear’s skin or fur long-term. And, finally, it must be able to withstand environmental stresses including extreme cold, water, salt-water, snow, and abrasions (caused by a polar bear rolling or rubbing against something).

Photo: Kt Miller/Polar Bears International

Arctic conditions present unique challenges for the tracking devices.

Q: What is the time frame for development? How soon do you expect to see a solution?

A: 3M scientists and engineers began with a brainstorming session in November 2018 and presented their initial ideas a month later. After that, they conducted research into the most promising concepts, working with fur swatches provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In 2020, much of the physical work was put on hold while 3M's employees worked from home during the pandemic. But the team modeled designs digitally, coming up with four strong solutions. Of the four, we chose two to be tested: the Tri-Brush and the Crimp Plate. Both have a “burr on fur” approach that allows the devices to latch onto a polar bear’s fur.

One of the four "burr on fur" prototypes designed to stick to a polar bear's fur.

Q: How are researchers testing the tracking devices?

A: We began testing the prototypes in the fall of 2020 on wild polar bears in the Western Hudson Bay population in cooperation with Manitoba’s Polar Bear Alert Program. In 2021, we also started testing the devices on polar bears in zoos and aquariums, working with partners in our Arctic Ambassador Center network.

Because zoo and aquarium settings are so diverse, they are ideal for testing the performance of the prototypes under various conditions, providing critical information that we would be unable to obtain from wild bears roaming in the Arctic. For example, if a tag didn’t stay on, what caused it to fail? Saltwater? Rolling in the snow? Play-wrestling with another bear?

So far, zoos have attached 11 tags to polar bears in their care, with keepers observing them every day to determine (1) whether the bear interacted with the tag and (2) whether the tag changed how the bear chose to interact with its environment or any other bears in the exhibit. Keepers also observed the bears daily to determine what behaviors might cause the tag to come off. Participating zoos reported no negative effects on the bears from wearing the tags.

Already, the zoo studies have yielded important information leading to both deployment and design modifications. For example, staff and animal care teams identified the middle of the shoulder blades as the best placement for a tag. Zoo findings also led to a slightly larger footprint for the Crimp Plate tags and a plastic cover for the Tri-Brush tags, providing more protection.

In the fall of 2021, we incorporated these design modifications into 12 tags that were tested on wild polar bears in western and southern Hudson Bay during the fall of 2021. The deployed tags transmitted in active mode on average for 53 days; the two longest durations were 100 and 114 days.

Next steps are to continue testing with zoo bears while also planning tests on wild bears in western and southern Hudson Bay in the fall of 2022.

Thanks to the work so far and support of partners, we are getting closer to proving a less invasive and reliable attachment method for tracking all polar bears. This will allow us to better understand this threatened species across their range and the changes they are experiencing in their declining habitat.

Q: How long will it take researchers to know if the devices work?

A: The testing phase could easily last a couple more years as we gather data on the performance of the prototypes and make design adjustments based on what we learn. The tracking devices are designed to transmit location information and other data for 270 days. Our goal is to develop a tag that can “stick” to the bear’s fur for that length of time, maximizing the data we retrieve. We’re not quite there yet—our best performance to date was 114 days on a wild polar bear—but we’ve made great progress since our first tests.

Even if don’t reach 270 days, anything over 30 days is useful for tracking bears that have been relocated. And anything beyond that will be a potential boon to research and monitoring as we build up data sets for subadult bears and males of all ages.

Q: Are there any other partners in this project?

A: In addition to staff and scientists from 3M and Polar Bears International (myself, Geoff York, and Alysa McCall), researchers from the University of Alberta (Dr. Andrew Derocher), the U.S. Geological Survey (Dr. George Durner), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Michelle St. Martin), Manitoba Sustainable Development, and the University of Washington (Dr. Kristin Laidre and Jennifer Stern) are providing expertise. Participating zoos include Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium, Kansas City Zoo, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, Assiniboine Park Zoo in Canada, San Diego Zoo, Como Park Zoo, Oregon Zoo, Louisville Zoo, Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, and Utah’s Hogle Zoo. The Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium's Dr. Holly Reed Conservation Fund and the Kansas City Zoo have provided funding.

Q: Any parting thoughts?

A: I’m excited that this project could provide a real breakthrough in how we study wild polar bears and the fact that it will be minimally invasive. Also, it’s an honor to have the opportunity to work with the 3M team, including my dad. The creativity and solutions-forward nature of these people are exactly what polar bears need. This is a volunteer project on the part of the company and it’s incredible to see the commitment on the part of everyone involved. I’m a gadget guy myself—I love finding ways to make technology work in Arctic settings—so this project is right up my alley.