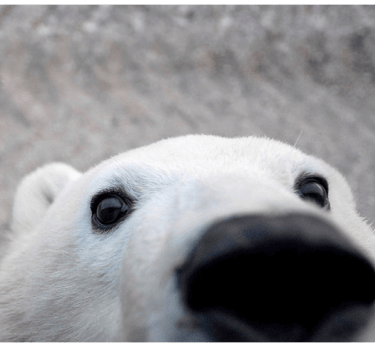

Hearing gunshots and a helicopter early one morning in Churchill, I looked up from folding laundry and peeked out the window. There was the Polar Bear Alert team, moving a polar bear from behind our house and away from town. Within minutes they had expertly moved the animal to a safer location, and I went back to bundling socks, but I couldn’t help but feel jolted by the stark reminder of what it’s like living with polar bears.

It had been a while.

Fall 2021 marked my first bear season back in Churchill since 2018, but it still felt like home. I was thrilled to see colleagues, chat with eager visitors, and watch the animals around which my work revolves. My visit was mostly spent breezily bouncing from town to tundra and task to task, but with the underlying seriousness that comes with living in a town that’s host to the world’s largest bear.

Back home in the Yukon we have black and brown bears, but I don’t reflexively look around every corner or under cars when strolling around my neighborhood. I walk differently in Churchill, though, because polar bears can be in town on almost any given day when Hudson Bay is ice-free. Currently the ice-free period is roughly July to November, but it’s getting longer.

Churchill’s polar bears, or the Western Hudson Bay population, are already spending 3-4 weeks longer on land than in the 1980s due to earlier sea ice break-up and later freeze-up, caused by a warming Arctic. On land, polar bears lack access to their main food source, seals, which they hunt via sea ice. During the ice-free period, polar bears lose up to 1 kilogram per day of fat while waiting for sea ice to return. Longer periods of time without ice leads to hungrier, and sometimes more desperate, animals who are more likely to approach human settlements looking for options.

Because of its long history with polar bears, Churchill has many resources, such as the provincial Polar Bear Alert Team, to help them handle their unique living situation. However, not every coastal community is well-prepared to handle polar bears, and some are facing a new reality. For example, the Southern Hudson Bay polar bears in Ontario are also spending more time on land. But communities there have not historically dealt with polar bears in their backyards and therefore do not have access to as many safety resources. And this is where our conflict-reduction efforts come in, working with communities as they choose solutions that work best for their unique situations.

In December 2020, a mom and cubs were relocated away from Moose Cree First Nation, Ontario, a community that had not faced this problem before. This spurred a call for long-term assistance in the face of rising polar bear encounters and, in December 2021, a community visit, supported by Polar Bears International, included:

Taking steps toward co-developing a plan for determining response(s) if a polar bear enters the community

Distributing printed materials on polar bear safety

Facilitating discussions with community leaders and residents about longer term solutions, such as moving or fencing the waste disposal site that attracted the polar bear family in the first place

Holding a nonlethal deterrent training workshop and tools for use in deterring polar bears

Providing funding in support of a bear monitor position

We plan to follow up on this visit with another in February and expand to other communities along the northern Ontario coast throughout 2022.

I am now home and back to folding laundry in peace, but I can’t help but think about the changes already happening for polar bears and for people in our warming world. Human-polar bear coexistence is an issue that will only continue to grow throughout the Arctic, so communities need to be empowered with tailored solutions but without bearing the entire burden.

Thank you to community and project partners including Moose Cree First Nation, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, York University, and Environment Canada and Climate Change.

Thank you also to funders of the “Detect and Protect” project, including the RBC Tech for Nature fund, working to develop tech solutions for dealing with increasing polar bear encounters.