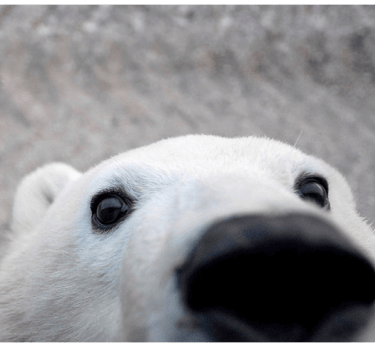

One of our research teams spent three weeks in Svalbard, Norway just before the coronavirus shutdown, where they took part in a maternal den study in partnership with San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance and the Norwegian Polar Institute. The study involves placing remote cameras at den sites to record the activity of emerging polar bear moms and cubs.

We caught up with BJ Kirschhoffer, our director of field operations, to learn more about the project and why it matters.

Q: First, could you tell us a little about polar bear moms and cubs in their dens?

A: It’s actually quite remarkable. Female polar bears dig dens in snowbanks in the fall and give birth to their cubs in late December or early January—a time of year when temperatures outside can plunge to -40. At birth, the cubs are blind, covered with light fur, and weigh roughly one pound. The cubs are quite vulnerable at that stage. They rely on their mother’s care and the shelter of the den for their survival. The family remains in the den for three or four months, hidden from view, until the cubs are strong enough to follow their mom to the sea ice in spring.