Svalbard, Norway is known for its world-class polar bear sea ice habitat in winter, but Svalbard summers are magical in their own right. The midnight sun dominates the sky during the polar summer, and day and night become one as the light shines equally bright around the clock. Summer brings a diverse range of wildlife–the archipelago is taken over by migratory birds for nesting, and an abundance of walruses, seals, and whales return to the fjords to feast on the bounty in the cold waters. Polar Bears International’s Photography Ambassador Daniel J. Cox of Natural Exposures shares exciting stories and photos from his Svalbard trip earlier this summer.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

Photographing Arctic Wildlife Under the Midnight Sun

7 MINS

01 Aug 2022

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

What is it like to photograph in Svalbard in summer?

Svalbard in the summer is absolutely delightful. The town of Longyearbyen is such a beautiful Arctic village. Those who have traveled throughout the Far North understand why Longyearbyen is so special. The streets are paved and clean, and the town has a great hospital, numerous beautiful hotels, good food, and excellent public transportation. Having all of these amenities is hard to believe on an island with 2,300 people located 650 miles from Norway’s mainland.

Getting out into the wild requires a ship. Ours was relatively small and agile, allowing us to go places larger vessels can't maneuver. At this time of year, there's not much ice on the archipelago's west side, so seeing bears on ice required visiting the fjords and bays that still held fast ice. Getting to the eastern side of the islands isn't possible this time of year due to too much ice.

A typical day started around 7:00 am if there were clouds, earlier if the skies were clear. Each day we spent most of our time searching the coastline as we headed north. Once we found a subject like a bear or a walrus, we would load the Zodiacs for a closer approach, always adhering to distance guidelines put forth by the Association of Arctic Cruise Operators. Being in a smaller vessel and approaching quietly and respectfully allowed us to get photos without bothering our subjects.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

What is it like to be under the midnight sun?

Working in the Far North above the latitude where the sun never sets is always exciting for a photographer. Beautiful imagery is all about light, and working above the Arctic Circle in the summer, sunlight is omnipresent. Whether direct from the sun or overcast clouds, creating photos when you should be asleep is a thrill.

Ideally, the best light happens when the skies are clear and the sun hangs low. If it's a cloudless day, the best work time is from around 10:00 pm to 4:00 am. The thick atmosphere blocks most blue light when the sun is just above the horizon. The rays that make it through are warm and golden.

On this trip to Svalbard, we had lots of clouds. Unfortunately, on this trip we had no beautiful light. I've included the image below, which I shot a couple of years ago, to show you how gorgeous Arctic light can be.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

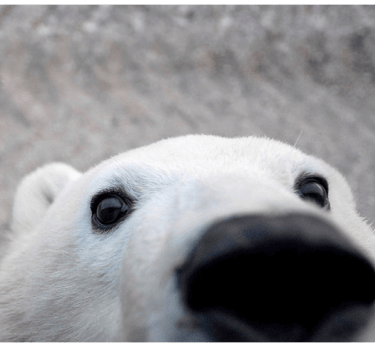

What was your favorite polar bear sighting?

My favorite polar bear sighting happened one morning when we found a mother with a pair of two-year-old cubs. They were walking along the beach, obviously on a mission. Eventually, the gravel beach ended near the edge of a glacier. All three paused, looking out across the water towards a group of small islands. The mother went first, followed by the largest cub, with the smallest hanging back. Eventually, all three slipped gently into the icy waters. We watched as they swam, their heads inches above the ocean. Finally, they came to the edge of the first island, and all three climbed the rocky outcrops, shaking water from their fur as they made their way up.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

It became apparent the islands were their destination. As the cubs climbed out of the water, you could see their pace quicken and excitement build. Each went in a different direction, sniffing the cracks and crevices, stopping briefly, and then bolting onward. They were hunting. Soon a female common eider jumped from one of the cracks where she was incubating eggs. Off she flew as one of the cubs scrambled to the ledge and buried his nose in the tundra. I couldn't see the actual consumption, but the yellow stains of yolk on the cub’s feet told the story. They were hunting for eggs, and they had found their first nest.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

Did you have any key wildlife experiences on the trip?

The polar bear family hunting for eggs on the islands was the most exciting event. I've heard of this behavior for many years but was never lucky enough to see it. On this day, I captured some images but still did not get what I feel are the quality pictures I'm hoping to see someday. But, that's what wildlife photography is all about. You don't always get the image you have in mind. And that's why it's so important to be able to go back to these locations until you can get the photos that help tell the story. That's what the Arctic Documentary Project is all about.

For those unfamiliar with the ADP, it's a separate fund under the nonprofit designation of Polar Bears International that helps underwrite our efforts to document the changes taking place in the Arctic, preserving a record while also highlighting this remarkable ecosystem. Donations to the Arctic Documentary Project allow us to travel to the Far North to capture the still photos and videos that help inspire support for polar bear and Arctic conservation. The imagery produced is available to Polar Bears International, their Arctic Ambassador Centers, and for educational purposes worldwide, at no charge.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

Another way to support the ADP is through the Natural Exposures Invitational Photo Tours my wife and I run. Some of our trips, like this photo tour to Svalbard, also happen to be a place of interest to the ADP. Our guests, who want to go to these areas, are effectively supporting Polar Bears International and the Arctic Documentary Project and our goal to document the Arctic. With our guests’ support, I can go to some places without taking funds from the ADP. That's a massive win for maximizing the funds donated to the ADP.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

Did you gain any great new additions to the ADP?

The best images for the ADP were probably of the couple of polar bears we encountered feeding on carcasses on shore. We don't know how they came upon the animals they were feeding on. Whether they captured them or the prey washed up on shore was unclear. Either way, it's an integral part of the story of how polar bears are doing their best to adapt. Typically the ice is where bears want to be; it's where they can hunt and have access to more prey. No amount of scavenging from shore will help them long-term, but it's essential to show these pictures as a record of how these bears continue to survive.

Other images I was relatively happy with are pictures of the beautiful eider ducks that live in the Arctic. Eiders are difficult to come by, and they're not why I go to Svalbard. But they are beautiful birds and add interest to pictures that excite viewers. As much as I love large mammals, like the polar bear, I'm also a big fan of birds, so I get excited about seeing these beautiful ducks you don't see further south.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox

We also encountered a blue whale. These animals are seldom seen in the waters off Svalbard. In fact, the Barents Observer wrote back in 2012, "Since the Norwegian Polar Institute began the Marine Mammal Sightings Database in 2005—which prompts scientists and tourists to record whale sightings in and around Jan Mayen and Spitsbergen, where the whales sometimes wander—just 74 sightings of the whale have been recorded, with only a single whale recorded in some years.”

But in the last few years, the Marine Mammal Sightings Database has recorded record numbers of blue whales—last year documenting several dozen whales throughout the summer season, when whales who winter in the Atlantic commute North in search of krill and plankton.

Seeing the largest living mammal on Earth was pretty exciting. If they are starting to appear more often in the north Atlantic, documenting those sightings can be beneficial.

Photo: Daniel J. Cox